Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has revolutionized the way engineers understand and optimize aerodynamic performance. From naval vessels slicing through waves to high-speed aircraft cutting through the skies, modern design relies heavily on virtual simulations rather than purely experimental testing.

In this article, we explore the core concepts behind CFD aerodynamics, examine the latest methodological breakthroughs, and illustrate how these tools drive innovation across marine, aerospace, and renewable-energy sectors.

The Foundations of CFD in Aerodynamic Analysis

At its essence, CFD solves the Navier-Stokes equations, mathematical expressions of mass, momentum, and energy conservation, to predict fluid flow behavior around complex geometries. Early CFD efforts were constrained by limited computational power, forcing simplifications such as inviscid or two-dimensional models. Today’s high-performance clusters and cloud resources enable fully three-dimensional, turbulent-flow simulations that capture subtle vortices, boundary-layer transitions, and wake interactions.

A typical CFD workflow begins with geometry preparation: creating a watertight digital model of the object, followed by mesh generation, where the computational domain is subdivided into millions or even hundreds of millions of discrete cells. Engineers then select appropriate physical models:

- Turbulence modeling ─ From Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) for steady-state approximations to Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) for transient, highly unsteady flows.

- Multiphase flow ─ When air, water, and sometimes additional phases (e.g., cavitation bubbles) interact, specialized solvers capture interface dynamics.

- Thermal coupling ─ In applications like gas turbines or high-speed craft, heat transfer between fluid and structure can critically impact performance.

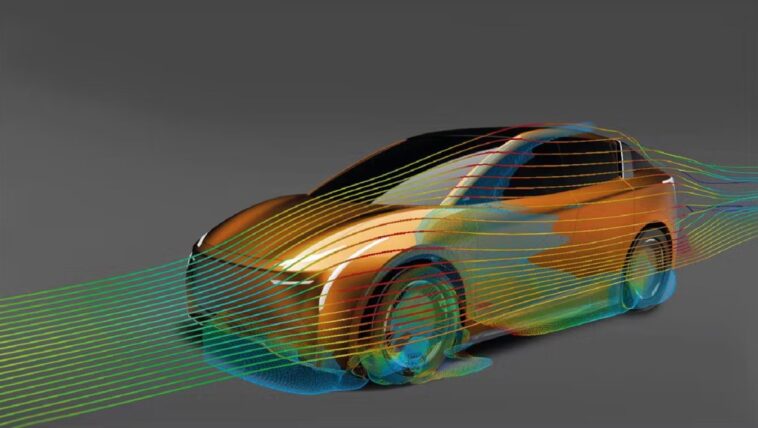

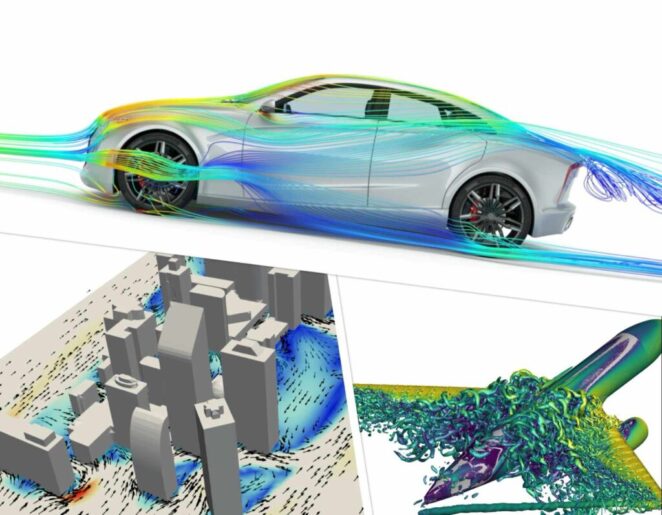

After specifying boundary conditions (inlet velocities, pressure outlets, wall roughness) and solver settings, the simulation iterates until residuals fall below convergence thresholds. Post-processing tools then visualize pressure contours, streamline patterns, and performance metrics such as lift, drag, and moment coefficients.

Key Benefits of CFD Aerodynamic Techniques

The rise of CFD aerodynamics owes much to its ability to:

- Accelerate Design Iterations

Virtual testing slashes reliance on costly wind, and towing-tank experiments. Engineers can explore dozens of design variants in the time it once took to build a single physical model. - Optimize for Multi-Objective Goals

Advanced solvers and multi-disciplinary optimization (MDO) frameworks enable simultaneous tuning of drag reduction, structural stress limits, and acoustic signatures, delivering balanced solutions tailored to mission profiles. - Reduce Risk and Improve Safety

Simulating extreme conditions exposes potential failure modes early in development, guiding reinforcement and control-system strategies. - Support Regulatory Compliance

Environmental regulations increasingly demand lower fuel burn and reduced emissions. CFD helps verify that vessel hulls and aircraft wings meet international standards before they ever touch water or sky.

Cutting-Edge Innovations in CFD Aerodynamics

Recent years have seen methodological advances that push CFD’s applicability further:

- Meshless and particle methods ─ Techniques like Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) eliminate the need for structured grids, excelling at highly deforming free-surface flows and fluid–structure interactions.

- Adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) ─ Solvers dynamically refine the mesh in regions of high gradient, such as shock waves or separation bubbles, ensuring accuracy where it matters most while conserving computational resources elsewhere.

- GPU-accelerated solving ─ Harnessing graphics-card parallelism has reduced simulation times from days to hours, making high-fidelity LES and DES practical for routine design work.

- Data-driven turbulence models ─ Machine-learning algorithms trained on experimental or high-resolution LES data generate closure models that outperform traditional empirical correlations, especially in complex, off-design regimes.

Real-World Applications Across Industries

Maritime Engineering

In the maritime sector, CFD aerodynamics plays a critical role, particularly for high-speed vessels and offshore structures exposed to wind. CFD tools enable the analysis of airflow interaction with superstructures, masts, funnels, and decks, optimizing designs to reduce aerodynamic drag, enhance stability, and minimize lateral wind loads. This leads to lower energy demands for course keeping, improved operational safety, and better performance in harsh weather conditions.

Aerospace Design

CFD underpins the development of airfoils, wings, and complete aircraft configurations. From laminar-flow control systems that delay boundary-layer transition to flutter analysis ensuring structural stability, virtual simulations guide every stage. Electric-propulsion startups also use CFD to optimize ducted fans and propellers for noise reduction and thrust efficiency.

Renewable Energy

Wind- and tidal-turbine developers deploy aerodynamic CFD to maximize power capture and fatigue life. Simulations forecast how blade designs respond to atmospheric turbulence or tidal currents, informing blade twist, chord distribution, and structural reinforcement strategies. Coupled aero-servo-elastic models further assess how control-system algorithms interact with flexible blades in variable flows.

Integrating CFD into the Engineering Lifecycle

Successful adoption of CFD aerodynamics demands more than software licenses. It requires a holistic integration into organizational processes. Best practices include:

- Centralized data management ─ Version-controlled repositories for geometric models, mesh templates, and solver settings ensure reproducibility and knowledge retention across teams.

- Automated workflows ─ Scripting mesh generation, case setup, and post-processing routines reduces human error and allows overnight batch runs of parameter sweeps.

- Validation & verification (V&V) ─ Regular comparison against experimental data towing-tank tests, flight trials, or scale-model tank experiments, builds confidence in simulation fidelity and highlights model limitations.

- Cross-disciplinary collaboration ─ Aerodynamicists, structural engineers, and control-system specialists must work in concert, using shared CFD results to inform decisions from material selection to sensor placement.

Future Directions and Challenges

As computational power continues its exponential growth, CFD aerodynamics will evolve in tandem. Anticipated trends include:

- Hybrid RANS/LES for industrial flow: Improved algorithms will make hybrid turbulence models faster and more robust, bridging the gap between quick RANS runs and highly accurate LES.

- Digital twins: Live coupling of CFD solvers with onboard sensor data promises real-time performance monitoring and adaptive control, ushering in a new era of predictive maintenance and operational optimization.

- Cloud-native CFD platforms: Scalable, pay-per-use CFD services will democratize access, enabling smaller firms to leverage high-fidelity simulations without heavy capital investment.

However, challenges remain. Ensuring that increasingly complex models remain transparent and interpretable is crucial to avoid “black-box” solutions. Data privacy and intellectual-property protection in shared cloud environments must also be addressed.

Finally, education and training will play a pivotal role: the next generation of engineers must be fluent in both the physics of fluid flow and the nuances of numerical methods.